In January 2017, 49-year-old Shiva Ganesh from Trichy, Tamil Nadu, working as an IT administrator in Singapore, received a notice from the Indian Passport Authority asking him to explain why his passport should not be cancelled. Alarmed, he sought to understand the issue but was instructed to visit the Indian embassy in Singapore. At the embassy, officials informed him that he was the third individual from Tamil Nadu facing a similar situation. They offered him some time to settle the matter if possible. Desperate, Shiva Ganesh wrote numerous letters to the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), but he received no response. “I didn’t know what else to do,” he said. Left with no options, he resigned from his job, returned to India, and surrendered his passport. Since then, Shiva Ganesh has been not only unemployed but also stateless, with no country to call his own.

Shiva Ganesh is one of the thousands of people born in Sri Lanka who sought refuge in India during the civil war of the 1980s. As a Tamil of Indian origin who fled Sri Lanka during childhood, he grew up, educated, worked, and started a family in India. Yet, he remains stateless, with no citizenship. His father was among the laborers taken from Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka in the 1940s to work on tea plantations. “During the civil war, we were in Kandy, Sri Lanka. Our house and my father’s shop were burned down. We were rescued by a few locals, and that’s how we reached Tamil Nadu in 1984,” he recalls.

Since his father was of Indian origin, Shiva Ganesh managed to obtain a passport in 1996. He initially went to Malaysia and later moved to Singapore for work, living a peaceful life much like any other ordinary Indian citizen. However, his life took a drastic turn following the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. All the Tamil people migrated to India during and before civil war came under intense scrutiny and thousands of them had to surrender their passports. Shiva Ganesh was no exception. His life has been a long and exhausting struggle since 2017 when he was forced to surrender his passport. “No company will hire me. My nationality has always been a question . I used to work as an IT professional specializing in security systems. Who would employ a stateless person in such a field?” he asks.

The name Shiva Ganesh is a pseudonym, as revealing his real identity could worsen his situation. Like him, most Indian origin Sri Lankan Tamils prefer to keep a low profile, living as inconspicuously as possible. They would not agree tagging them as refugees, identifying instead as repatriates because their ancestors were originally from India. Sri Lanka was merely a stopover for one or two generations, brought there by British rulers to work on tea plantations.

“His 15 year old son may also face the same predicament,” says Advocate Romeo Roy Alfred, a lawyer at the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court who has been providing legal aid to people like Shiva Ganesh. “The boy’s citizenship status is in question since one parent must be an Indian citizen and the other cannot be an illegal migrant. Although his wife is an Indian citizen, Shiva Ganesh’s status complicates matters. Proving he isn’t an illegal migrant is challenging.”

Despite coming to India from Sri Lanka with proper documentation, Shiva Ganesh’s current status remains uncertain.

For 57-year-old Nandakumar born in Sri Lanka in 1967 and forced to flee to India with his parents in 1985, the civil war is etched in memories of the acrid smell of burning, the sounds of shelling and gunfire, and the trauma of a violent mob pelting stones at his home. He recalls his once-picturesque village surrounded by lush green tea estates. His grandfather was among the thousands of Tamils recruited by the British in the early 1940s to work as laborers on tea plantations.

Statelessness begins in 1948 by the inactment of Cylon Citizenship Act 1948

Nandakumar’s statelessness did not begin with his arrival in India. His father, despite living in Sri Lanka, was never granted citizenship. Like him, many Indian-origin Tamils in Tamil Nadu have endured generations of statelessness. This plight dates back to 1948, with the enactment of the Ceylon Citizenship Act by the Sri Lankan government. This law, introduced shortly after Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) gained independence from British rule, effectively stripped nearly a million Indian-origin Tamils of their citizenship, leaving them marginalized and without a nation to call their own.

The Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948 was a landmark law in Sri Lanka that had profound consequences for the Indian Tamil community. Passed soon after Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) gained independence from British rule, the Act effectively denied citizenship to a large population of Indian Tamils who had migrated to the island during the colonial era.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, British colonial rulers brought significant numbers of Indian Tamils to work on Ceylon’s plantations. By 1946, their population had grown to approximately 780,000, representing about 11% of the total population. However, their increasing presence was perceived as a threat by the Sinhalese majority, which made up around 69.4% of the population. This perception sowed the early seeds of ethnic tensions in Sri Lanka.

The Indian-origin Sri Lankan Tamils who fled to India during the civil war represent the second or third generation of individuals who had already been denied citizenship. For most of them, their parents and grandparents were stateless, having been stripped of their citizenship under the Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948. This statelessness persists into the fourth generation—children born and raised in India, like the sons of Shiva Ganesh and Nandakumar, who have no ties to Sri Lanka. Citizenship laws in both India and Sri Lanka have left four generations of these families without a nationality.

Currently, an estimated 50,000 repatriates live in refugee camps, and 34,000 reside in individual houses across Tamil Nadu. While the Tamil Nadu government has adopted a lenient approach toward the Tamil population from Sri Lanka, granting them Aadhaar cards, ration cards, PAN cards, and driving licenses, these documents do not resolve their statelessness. Refugees in camps are issued identity cards tied to their camp addresses, but obtaining a passport—the ultimate proof of citizenship—remains an unattainable dream for them.

Citizenship and Statelessness within one family

Even within families, citizenship statuses can vary. Take the case of Nalini Kripalan, considered the only “success story” among Sri Lankan Tamils in Mandapam camp in Ramanathapuram District, one of the largest refugee camps. After years of legal battle, Nalini’s citizenship application was approved, and she obtained a passport. Her parents fled to India during the civil war, and she was born in Mandapam camp in 1986. Initially, her application was rejected because her parents were considered Sri Lankan nationals. However, her parents, too, were stateless, victims of the Ceylon Citizenship Act that denied citizenship to Indian-origin Tamils in Sri Lanka.

Nalini’s breakthrough came under the provisions of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1955. The Madras High Court ruled that she was eligible for citizenship based on Section 3(1)(a) of the Act, which grants citizenship to anyone born in India between January 25, 1950, and July 1, 1987. Since Nalini was born in 1986, she qualified. However, her younger brother, born in 1988, remains stateless, as he falls outside the specified cut-off date. Nalini is the only person having citizenship in her family. Every one including her husband continues to be stateless.

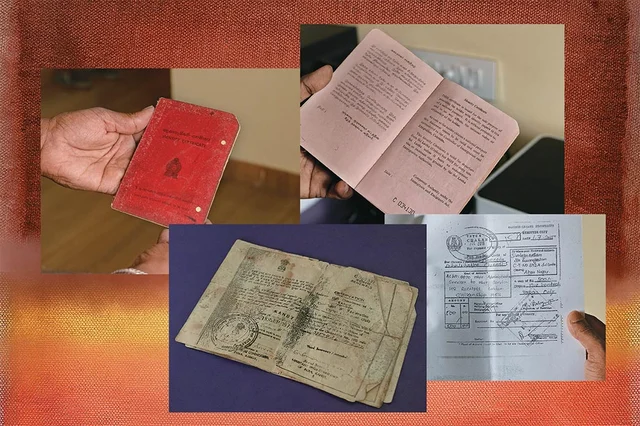

Seventy-five-year-old Marimuthu, born in Sri Lanka, is another victim of the civil war who migrated to India in 1985. He travelled with a ‘red passport’ a temporary, one-time travel document issued by the Sri Lankan government to the Indian origin Srilankan Tamils. Upon arriving, he settled in Trichy, Tamil Nadu, where his family had ancestral roots. At the time, Sri Lankan Tamil refugees were required to register at the nearest police station and renew their registration periodically.

A few years after his arrival, officials informed Marimuthu that registration was no longer necessary. He was made to believe that he was like any other Indian having Tamil Nadu as their mother land . Having an Aadhaar card and ration card in possession, Marimuthu believed he was an Indian citizen. For this elderly and uneducated man, understanding the difference between being a citizen and being stateless remains a complex and confusing matter.

Marimuthu has four daughters and a son, but only two of his daughters, born in India, hold Indian citizenship. The other three daughters were forced to surrender their passports after the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. While the two India-born daughters possess passports, the rest of the family—three siblings and the elderly parents—remain stateless. Among the seven members of Marimuthu’s family, only two are recognized as Indian citizens, while the others live in legal limbo.

The impact of the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi

The assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in 1991 had a lasting impact on the lives of Sri Lankan Tamils living in Tamil Nadu, as they came under intense scrutiny. “Every individual with ties to Sri Lanka became a suspect,” says Shanmuganathan, a local journalist who has extensively covered the issue of Indian origin Sri Lankan Tamils migrated to India. Until that point, these people were in the process of integrating into Indian society and were considered Indian citizens, with many even obtaining passports. However, after Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, the authorities launched a massive operation, and many were asked to surrender their passports. In Trichy only, for example, 3,000 people were summoned to surrender their passports on a single day and were stripped of their citizenship status.

According to Advocate Romeo, successive Indian governments, even during Jawaharlal Nehru’s time, failed to effectively address the issue of Indian-origin Sri Lankan Tamils. “The repatriation of nearly six lakh Indian-origin Tamils from Sri Lanka was an obligation under the 1964 and 1974 agreements between the two countries, but this obligation was never fulfilled. When the civil war broke out, there was a mass exodus of people to India, including Sri Lankan Tamils who fled to escape ethnic violence. These people were all placed in refugee camps together, but no effort was made to distinguish between Sri Lankan-origin Tamils and Indian-origin Tamils. Those who arrived in India with legal documents were wrongly categorized as refugees,” says Romeo.

The amendments to the Citizenship Act of 1955 further worsened the situation of these people. Even the fourth generation, like Shiva Ganesh’s 15-year-old son, is excluded from citizenship due to these changes, which narrowed the eligibility criteria. Under the 2003 amendment of the Act, one parent must be an Indian citizen, and the other must not be an illegal migrant. For most Indian-origin Sri Lankan Tamils, who are victims of ethnic conflict and civil war, proving that they are not illegal migrants is a nearly impossible task.

Brilliant discourse! Dinosaur Game embodies the intersection of nostalgia and innovation.